Lab 3: FPGA Video Controller and Sound Generation

Objectives

- Take at least two external inputs to the FPGA and display them on a screen

- React to an external input to the FPGA of their choice and generate a short ‘tune’ consisting of at least three tones to a speaker via an 8-bit DAC

Teams

Team 1 (Graphics): Ayomi, Emily, Eric

Team 2 (Acoustic): Drew, Jacob, Joo Yeon

Graphics

Setup

For our setup, we had to connect the FPGA to the monitor. To do this, we used a VGA connector that connects to GPIO pins xxx on the FPGA, and then a VGA cable to connect the FPGA to the VGA switch. The VGA switch allows us to go between the computer and the FPGA input.

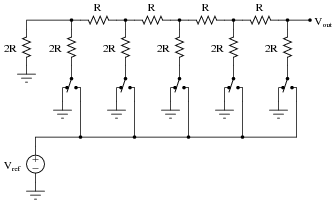

Since the VGA cable is composed of three analog wires and the FPGA produces a 3.3V digital output, a resistive 8-bit Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC) was provided. Using the DAC, the 8-bits for each color signal (3 red, 3 green, 2 blue) from the FPGA are converted into the three different RGB color 0-1V analog signals.

The resistor values chosen for the VGA connector are based upon the R-2R DAC resistor network which directly converts the parallel FPGA digital signal into an analog output.

(Credit: https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/worksheets/digital-to-analog-conversion/)

For red and green, since the signals are 3 bits wide, the resistor values chosen were approximately 270 Ohm, 550 Ohm, and 1200 Ohm. This is because 1200 Ohm is approximately twice 550 Ohm, and 550 Ohm is approximately twice 270 Ohm. Likewise, for the blue, since the signal is 2 bits wide, the respective values are 270 Ohm and 550 Ohm.

Simple Drawings

The first thing we wanted to work on after setup was to draw a simple image. From the template code for the VGA driver, we figured that the two synchronizing clock signals HSYNC and VYSNC would drive the output on the screen and output the x and y coordinates for the next pixel. The color of the corresponding pixel would be determined by the three RGB analog signals.

The block diagram below demonstrates how the FPGA code interacts with the VGA display.

(Credit: ECE 3400 course website)

Using what we had learned, we were able to split our screen in half and set them as two different colors, and also draw a basic square in the top left corner of the screen as shown.

Memory System for Blocks in Grid

Once we were able to draw a single square, we then needed to implement an array in order to store color values for the inclusion of multiple squares. For this, the 2x2 8-bit grid_array was used to store 4 different colors. Instead of using if-statements to determine which color in grid_array to select, we used the binary properties of the X and Y coordinates. The 7th index of our position variables is 0 within 0-127, 1 within 128-255, 0 again within 256-383, and so on . These binary values were to selected indexes in grid_array, assigning the color at each pixel and creating a repeating pattern of 128x128 pixel squares. Later, a conditional statment was added to filter out the repeating pattern. The resulting code and image can be seen below.

if (PIXEL_COORD_X[9:8] ==2'b0 && PIXEL_COORD_Y[9:8] == 2'b0) begin

PIXEL_COLOR <= grid_array[PIXEL_COORD_X[7]][PIXEL_COORD_Y[7]];

end

else begin

PIXEL_COLOR <= `BLACK;

end

Now to prepare for external inputs, the wires highlighted_x and highlighted_y were connected to GPIO_124 and GPIO_126. Before assigning PIXEL_COLOR, it checks if it is within the highlighted region. If so, the color will be red, rather than its grid_array color.

if (PIXEL_COORD_X[7] == highlighted_x && PIXEL_COORD_Y[7] == highlighted_y) begin

PIXEL_COLOR <= `RED;

end

Communcation method between Arduino and FPGA

To communicate between the Arduino and the FPGA, the first thing we did was to write a program that reads whether the input pin is high or low, and to output that to another pin.

pinMode(5, INPUT);

pinMode(6, INPUT);

pinMode(3, OUTPUT);

pinMode(4, OUTPUT);

if (digitalRead(5) == HIGH){

digitalWrite(3, HIGH);

Serial.println("Pin 5 = 1");

} else {

digitalWrite(3, LOW);

Serial.println("Pin 5 = 0");

}

if (digitalRead(6) == HIGH){

digitalWrite(4, HIGH);

Serial.println("Pin 6 = 1");

} else{

digitalWrite(4,LOW);

Serial.println("Pin6 = 0");

}

We tested that by printing to the serial monitor. Once we knew everything was working, then we built our voltage divider, so that we could connect the Arduino to the FPGA.

Voltage Divider

We had to build two voltage dividers, one for the x-coordinate pin and the other for the y coordinate pin. To build the voltage divider, we used a 1k and 2k resistor because 5V * (2/1+3) = 3.3V, which is the amount of voltage the FPGA operates at. Once we built the voltage divider. We uploaded the code to the arduino, and wired everything.

We connected the output pins, so that they would be the inputs into the voltage divider. We then connected the outputs of the voltage divider to the pins on GPIO_131 and GPIO_133. We moved the wires on the breadboard from high to low so that we could test move the square around the screen.

Acoustics

GPIO Setup and Square Wave Generation

We imported the template given in the lab handout as a starting point for our Direct Digital Synthesis. This only requried us to map our pins and wire the up the FPGA outputs. To make our lives easier, we mapped the 8-bit output to pins 9-23 odd on the FPGA on GPIO 0. Here the DDS_DRIVER module implementation within the DE0_NANO module:

DDS_DRIVER dds(

.RESET(reset),

.CLOCK(CLOCK_25),

.DAC_OUT({GPIO_1_D[23], GPIO_1_D[21], GPIO_1_D[19], GPIO_1_D[17], GPIO_1_D[15], GPIO_1_D[13], GPIO_1_D[11], GPIO_1_D[09]})

);

We then took the output from the FPGA and used an 8-bit DAC to convert the signal from an 8-bit representation to a voltage level from 0-3.3V (shown below).

After setting up the GPIO pins with the DAC, we were ready to create a square wave. In the DDS_DRIVER module, we toggled the output from low to high at a specific frequency. Since the DE0_NANO module uses a 25 MHz clock, we had to find a way to reduce the frequency at which we outputted the square wave. In order to do so, we used the following always block. The key is a counter that counts up to 1000 (thus only toggling the output once for every 1000 positive edges of the clock). This translates to a 25 MHz / 2 / 1000 = 12.5 kHz signal. The factor of two comes in because we are only toggling at the positive edge of the clock, not on both edges. When the counter hits 1000, we reset it and toggle output; otherwise, we simply increment the counter.

always @(posedge CLOCK) begin

if (RESET) begin

OUT <= 8'b0;

counter <= 32'b0;

end

else begin

if (counter == 32'd1000) begin

counter <= 32'b0;

OUT <= ~OUT;

end

else counter <= counter + 1;

end

end

Here is the square wave that this code outputs (we forgot to take a video, but we hooked a scope up to the FPGA output):

Sine Table Generation

We generated a table of a single period of a sine wave, with 256 points ranging from 0 to 255 using python:

for i in range(256):

print(hex(int(127*sin(2*pi*i / 256) + 128))[2:].zfill(2))

We saved the output to a file, which synthesized into a Verilog ROM:

module sine_rom

#(parameter DATA_WIDTH=8, parameter ADDR_WIDTH=8)

(

input [(ADDR_WIDTH-1):0] addr,

input clk,

output reg [(DATA_WIDTH-1):0] q

);

// Declare the ROM variable

reg [DATA_WIDTH-1:0] rom[2**ADDR_WIDTH-1:0];

// Initialize the ROM with $readmemb. Put the memory contents

// in the file single_port_rom_init.txt. Without this file,

// this design will not compile.

// See Verilog LRM 1364-2001 Section 17.2.8 for details on the

// format of this file, or see the "Using $readmemb and $readmemh"

// template later in this section.

initial

begin

$readmemh("sin256.txt", rom);

end

always @ (posedge clk)

begin

q <= rom[addr];

end

endmodule

DDS

The Direct Digital Synthesis (DDS) module inputted counter[31:24] and CLOCK to the sine table module and connected the output to the DAC_OUT.

sine_rom #(8, 8) sineTable(counter[31:24], CLOCK, DAC_OUT);

We used only the highest bits of the counter as the address. This is because the sine table was 256 entires long, but counter was a 32 bit integer. By making coutner a 32 bit integer however, we get significant frequency rage. By modifying the increment, the amount by which we incremented counter each 25 MHz clock tick, we could control the frequency output. The increments were calculated according to the following formula:

Where phi is the increment, f is the desired sine output frequency, and f_s is the sampling frequency. The verilog block for doing this increment is:

always@(posedge CLOCK) begin

if (RESET) begin

counter <= 0;

else begin

counter <= counter + increment;

end

end

Scale Generation

Once we got pure sine generation working, we added the capability to play arbitrary frequencies in sequence. For that, we used another python script:

#! /usr/bin/env python3

import sys

if __name__ == '__main__':

with open(sys.argv[1]) as f:

for line in f.readlines():

print(hex(int(2**32*float(line)/25e6))[2:].zfill(8))

We ran this script on an input file consisting of the frequencies of the notes in a C scale, and it produced a file containing the DDS increments in hex. Then, we synthesized that into another Verilog ROM, just as above. The DDS module then incremented the index into the increment ROM every second, causing the output frequencies to change to the desired frequencies. With this, we played a C scale:

Playing Arbitrary Songs

While we didn’t have time for this lab, we can easily generalize the scale approach above to play (at significantly reduced quality) any song. To do so, take the song, and break the samples into groups of some fixed length, probably 0.1 s. Take the Fourier transform of each section, and select the dominant 8 frequencies. Assemble these into a file with 1 frequency per line (8 lines of frequencies that occur at the same time, then the next 8, and so on). Run the increment generation script on the file. Then, modify the Verilog code to instantiate 8 DDS modules, each one reading from a different initial index in the increment file, and incrementing the index by 8 each each 0.1 s. Average the outputs from all 8 (which is not as not that bad: sign extend all to 11 bits, add them, and then bit shift the result right by 3 bits). Output this to the DAC.

Verilog Style

We decided against having a finite state machine considering the fact that our code was very short and not hard to follow. If we needed more code and/or states, it would have certainly made sense to break everything up, but we were able to accomplish the task efficiently. A finite state machine would have only complicated things in this case.

Work Distribution

- Ayomi: Wrote the Arduino code for the the x,y input from Arduino to FPGA

- Drew: GPIO setup and Square wave generation

- Emily: Initial box drawings

- Eric: Mapping of pixel coordinates

- Jacob: Sine tablem, scale generation, and playing arbitrary songs

- Joo Yeon: Tone generation